Discussion Paper 7 - Shifting Trust and Satisfaction: Tracking Democratic Resilience after Australia’s 2025 Election

Biddle, N., (2025) ‘Shifting Trust and Satisfaction: Monitoring a Key Dimension of Democratic Resilience in Australia (October 2024 to May 2025)’ Australian Resilient Democracy Research and Data Network Discussion Paper 7, Australian National University.

Key Takeaways

Following the 2025 federal election, Australians reported increased satisfaction with democracy and higher trust in key political institutions — a post-election “democracy bounce.”

While overall confidence in the electoral process remains strong, concerns about media fairness and data misuse continue to affect perceptions of legitimacy.

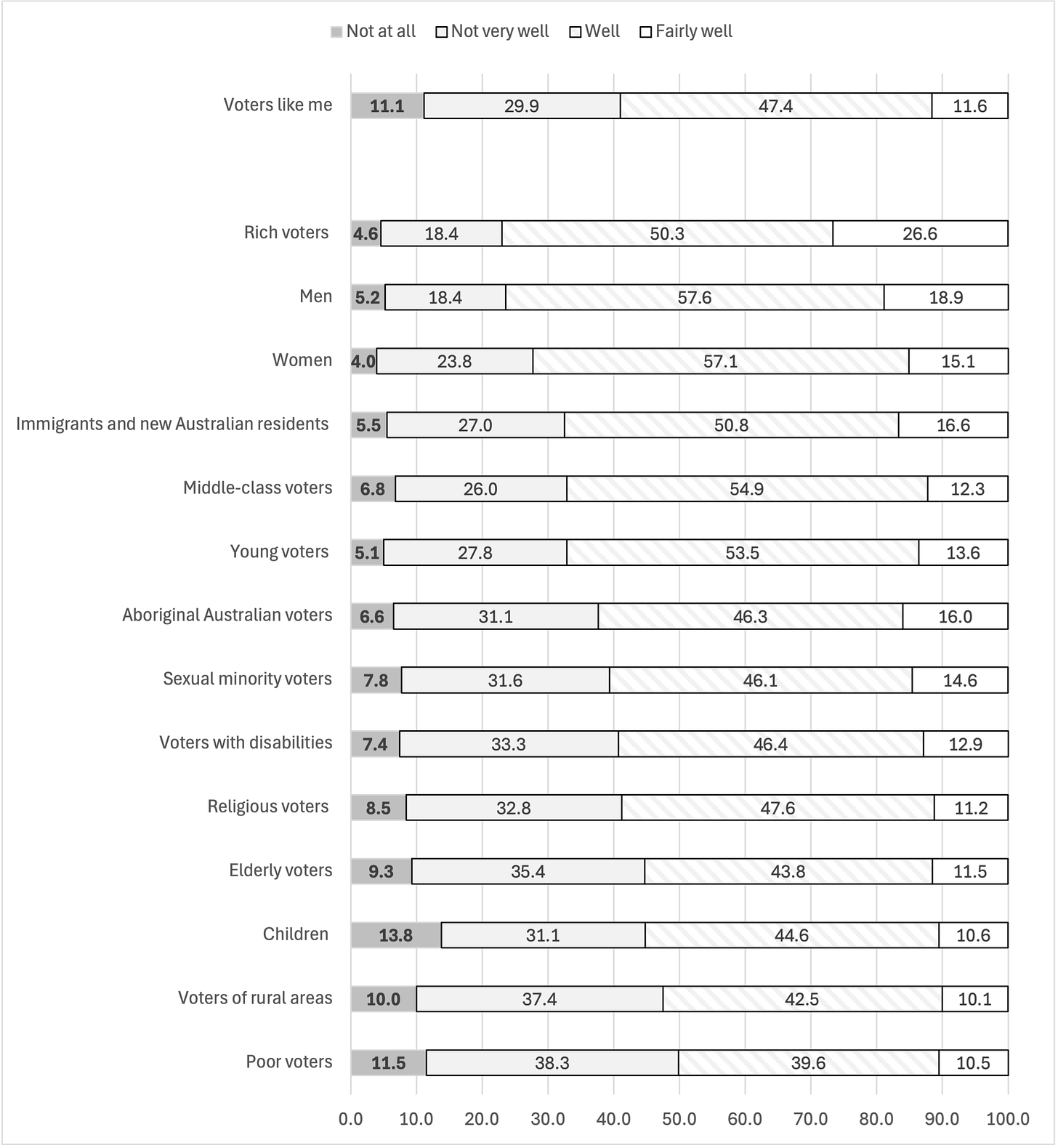

There are clear gaps in perceived political representativeness, particularly among voters with lower education levels, lower incomes, and those who did not vote for the governing party.

Monitoring these trends over time is critical to strengthening Australia’s democratic resilience in an era of polarisation and institutional distrust.

Context

At a time when democracies globally are under strain, Australia’s 2025 federal election offered valuable insights into how national events can shape public trust and satisfaction. Using data from the 2025 Election Monitoring Survey Series (EMSS), this paper examines how Australians viewed democracy, political institutions, and the conduct of the election — and how these attitudes shifted across four survey waves from October 2024 to May 2025.

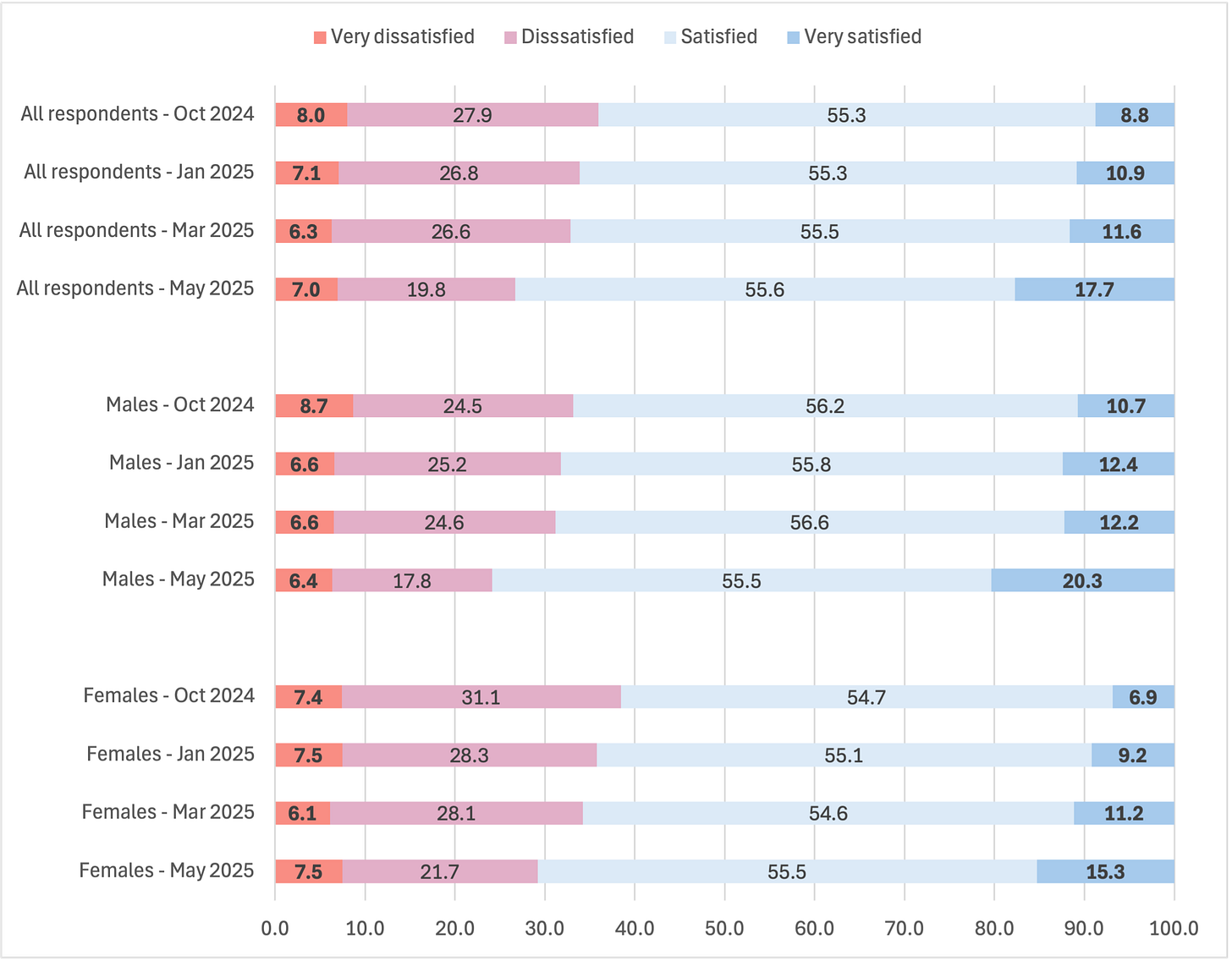

The findings suggest that elections remain a critical inflection point in public perceptions of democracy. Satisfaction with democracy reached 73.3 per cent after the election, an increase from 64.1 per cent as the election campaign was about to get started.

There were corresponding increases in trust toward the federal government, Parliament, and political parties. At the same time, concerns about media fairness, data misuse, and representation for lower-income Australians indicate ongoing risks to democratic resilience.

Key Challenges

Persistent Disparities in Trust and Representation: Lower trust is evident among Australians with lower education and income levels, and among those experiencing financial stress — key vulnerabilities for democratic resilience.

Polarised Perceptions by Partisanship: Voters for non-governing parties (especially Coalition and minor party voters) report lower satisfaction with the election process and less confidence that Parliament represents them — highlighting the importance of managing political polarisation.

Information Integrity Risks: Concerns around media bias and data misuse by candidates remain high. Only 10.1% of Australians believe journalists provided fair election coverage “very often,” and nearly one in five believed personal data was misused “very often.”

Representation Gaps: While many Australians believe Parliament represents “people like me,” the group seen as most represented remains “rich voters” — underscoring ongoing concerns about perceived equity in political representation.

Strengthening Democratic Resilience: A Research and Policy Agenda

To build on the post-election gains in trust and satisfaction, policymakers and democratic institutions should in the longer term prioritise:

Monitoring civic sentiment more frequently and responsively

Rather than relying solely on annual national surveys, there is value in tracking democratic satisfaction and concerns at more regular intervals—particularly before and after major events such as elections, crises, or major policy reforms. While average levels of trust or satisfaction may remain stable, shifts in the distribution of concerns, priorities, or engagement levels can offer early signals for policymakers and community leaders.Using civic data to guide what can be done, not just what is happening

Socioeconomic correlations with civic trust and participation help identify disparities, but they don’t offer clear direction on how to respond. Survey data can point to where issues are emerging or who is being affected, but alternative data sources are needed to understand why and what to do next. This underscores the need for community-level administrative data, place-based community input and deliberative follow-up methods embedded in ongoing democratic monitoring and complements to survey methods.Addressing Economic and Social Drivers of Distrust. Policies to reduce financial stress and inequality can have a measurable impact on trust in democracy. As the EMSS findings show, financial wellbeing remains strongly linked to satisfaction with democracy and government.

Three areas for near-term policy focus are:

Information integrity: Public concern about misinformation is high. Efforts to strengthen safeguards must be matched by strategic, transparent communication that helps the public understand what actions are being taken—not just the threats themselves.

Perceptions of voice and representation: Trust is closely tied to whether people feel heard. We need deeper insight into the moments and mechanisms through which people feel represented—or excluded—and how this varies across communities and institutional settings.

Design with responsiveness in mind: Policy and program design should account for civic feedback mechanisms. Institutions that can detect and respond to shifting public concerns in real time are more likely to sustain legitimacy in an era of rapid change.

Conclusion

The 2025 election provides encouraging evidence that Australia’s democracy remains resilient: satisfaction with democracy rebounded, and trust in key institutions improved. But resilience is dynamic — not static — and the underlying risks of polarisation, inequality, and distrust must be actively managed.

By monitoring these trends in real time and responding with inclusive, transparent governance, Australia can continue to strengthen the foundations of democratic resilience in the years ahead.